Lawrence Kendall Jackson

WWII Fighter Pilot

WWII Fighter Pilot

Lawrence Kendall Jackson was born to Edith and Ira Jackson on March 17th, 1921 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Edith died when Lawrence was only four. His father Ira was a traveling salesman and there was no way he could earn a living and properly care for his children. In the 1920s there was no social safety net, and Ira’s only choice was to place the children in an orphanage. Those who ran the orphanage, not wanting to upset the majority of kids who were without parents, would not let Ira visit. Lawrence’s only respite were the odd times when his father, through the perimeter fence, could talk to him. Regardless, Lawrence made the best of it and did well at school. By his own admission, he was not an athlete but enjoyed swimming, cycling and softball as well as hunting and fishing. In 1937 he completed grade ten at Mineville High School then finished his last two years at the Halifax Technical College.

Lawrence, & his wife who was a nurse at Toronto General Hospital

Lawrence visiting home on leave

By his late teens Lawrence had decided that a career in the Air Force was something to strive for. In January of 1939 he applied for the Royal Canadian Air Force, and was rejected, as he probably expected. Prior to the outbreak of World War II the Royal Canadian Air force had no modern planes, was underfunded and understaffed. Very few people that applied were accepted. Unfazed, Lawrence applied to work as a civilian clerk for the Royal Canadian Navy at the Halifax Naval Base. He worked there for a year while attending the Halifax Technical College. He was still working there when WW II broke out in September of 1939. With the outbreak of WW II the RCAF was quickly expanded, however there was still a requirement to be a university graduate in order to become a pilot. On April 26th , 1940 Lawrence was accepted into the RCAF. The intake officer described him as a person of above average character and a very neat appearance, however at 5'7" and 135 he was not a large man. His previous experience as a ledger clerk for the navy meant that, much to his disappointment, he was given this same job in the RCAF at RCAF Station Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, . His hope for a world adventure had instead dropped him within sight of his old job across the harbour. The only bonus was that as a “technical” tradesman he was immediately promoted to Cpl.

As the Battle of Britain took its toll on aircrews during the dark years of 1940 both the RAF and the RCAF realized that they were in dire need of pilots. By late 1940 they had unceremoniously dropped their university requirements. Lawrence applied to re-muster as a pilot and in August of 1942 Lawrence’s real adventure began when he was accepted as a pilot candidate. Finally given his chance he showed his abilities were far above those of a mere clerk. Thousands of men applied for aircrew and few were accepted. Of those almost all wanted to be pilots. Only a few of them were accepted to be pilots, most becoming Navigators, Bombardiers or Air Gunners. Of those chosen to be pilots, only the elite were put forward for training as fighter pilots. Lawrence so impressed his instructors that he was chosen to be a fighter pilot.

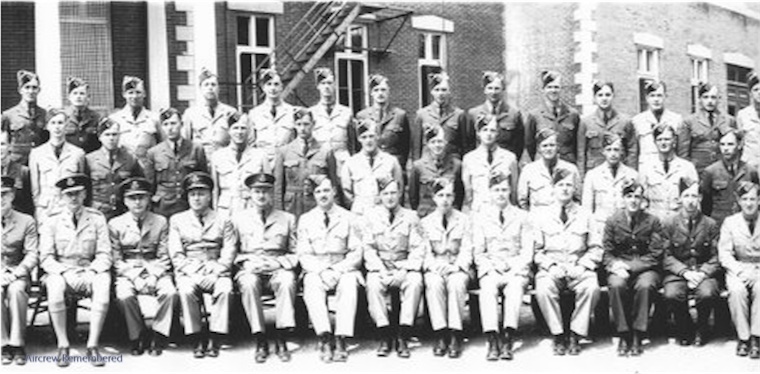

Lawrence in flight training at Victoriaville Quebec, June 1942. He is front row, third from right.

On November 21st , 1942 he reported to the # 4 Elementary Flight Training School at Windsor Mills, Quebec. There he learned the basics of flying, along with other pilots from the U.K., New Zealand, Australia and other Commonwealth countries under the auspices of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Upon completing ground school he took his first flights in the diminutive Tiger Moth biplane. It was in this plane that he made his first solo. On March 19th 1943 he and his fellow students formed up for morning parade and there on the parade square he was awarded his coveted pilots Brevet (badge). On the 1st of April 1943 he moved to the # 13 Secondary Flight Training school at St. Hubert, Quebec, just across the river from Montreal. Here he honed his skills on the larger and more powerful Harvard, a plane much more like the modern fighters he would soon have to handle. Now a confidant and much admired pilot, he met a pretty nurse back at Halifax and on April 24, 1943 he married Dorothy Ada Schuman, who was working at the Halifax General Hospital. After Lawrence shipped out overseas she moved to live and work at the Toronto General Hospital.

By March of 1943 Lawrence was ready to go overseas. He received his final assessment in front of his commanding Officer, and it was then that he was told he was to receive a King’s Commission. This meant a leap forward in rank from Sergeant to Pilot Officer. Of all the pilot inductees only the top 10 % became fighter pilots. Of those, only the top 10 % were thought worthy enough (and showed enough leadership potential) to become officers. The man who had applied to be a clerk in the RCAF and been rejected in 1939 had come a very long way.

After a nervous one week ship voyage through the U-Boat infested North Atlantic Lawrence arrived in England. There he received his overseas indoctrination and by July he was at the # 7 Advanced Flying unit where he prepared for the final stage of his training, flying front line fighter aircraft like the Spitfire and Hurricane. He was posted to the # 57 Operational Training unit on June 27th, 1944 where he finally took the controls the Hawker Hurricane single seat fighter. By this stage of the war D-Day had already occurred. The Hurricanes had been phased out and much of the Luftwaffe had been destroyed. The pure dogfighting fighters, like the Spitfires, were in a lot of ways out of work by then. Left to escorting Bombers over occupied France, they were unable to go into Germany due to there short operational range.

The replacement from Hawker for the Hurricane, the new Typhoon was now being delivered to the Royal Air Force. The Typhoon had gone thorough a number of years of problems and had come very close to being canceled. It was a very powerful, large fighter, and it was very difficult to fly. Only an experienced and confident pilot could get the most out of one. Prior to the invasion of Europe it had become obvious to the RAF that they would need a new breed of fighter, one that was suited more for attacking tanks, trains and other ground targets than pure air to air combat. The Typhoons power and ruggedness made it the obvious choice. They sported 4 x 20 mm cannons and were the first planes to use the new air to ground rockets, fired from rails on the wings. These ground attack planes struck fear into the German army, and many credit them with the defeat of the German armoured divisions after D-Day. However, ground attack was also the most dangerous assignment for a fighter pilot, as anti-aircraft fire was often thick and lethal.

Lawrence sitting on the wing as his ground crew prepare his Typhoon with an extra special message for the Nazis.

Rather than being posted to an RCAF Spitfire squadron, the diminutive (and newly promoted) Flying Officer Lawrence, was posted instead to 182 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, under the command of a South African, Major D.H. Barlow. 182 Squadron were equipped with the fearsome Typhoon. When he reported for action on October 20th, 1944 182 Squadron had already left England and were located at a temporary airfield (B6) at Coulombe, just south of Caen, France. From here the Typhoons wasted no precious fuel crossing the English channel, but could rather lift off and be in action in minutes. They would often take off fully armed and circle in the rear area waiting for the Army to call for assistance in destroying German troop formations at the front. The Squadron flew innumerable missions throughout the terrible winter of 1944. After the allied armies had moved so far forward that the Coulombe base was no longer close enough, the squadron moved to a new temporary base (B86) near the German border at Helmond in the south of Holland. Here the Squadron pilots were lodged in the impressive Christus Koning building not far from the airfield.

In the late Spring of 1945 the squadron relocated to B164 at Schleswig where they pressed home attacks on the German Army as it retreated further into Germany. On April 19th, 1945, the squadron received orders to attack enemy shipping on the Elbe river northwest of Berlin. As the flight passed over the town of Brandenberg they dove to attack ships on the river, streaking down firing cannons and rockets. On the return leg the Squadron spotted a small formation of German Tanks near Bleckwedel and attacked. As they pulled up to break off Lawrence’s Typhoon (# SW 412 ) was hit by anti-aircraft fire and his damaged aircraft slowed and fell behind those of his squadron mates. He called the flight leader on the radio and advised that he was damaged and was about to bail out. They did not hear from him again. Like many pilots, Lawrence could not see the extent of the damage to his Typhoon from the cockpit. Shortly after his radio transmission it exploded and he was killed instantly. The wreckage came down near the small town of Wusterhausen. The war ended two weeks later. The man who had started the war as a clerk finished it as a dashing Typhoon pilot giving his life for his country and the fight against fascism.

Flying Officer Lawrence Kendall Jackson is buried with many fellow Canadians at the beautiful and immaculately kept Becklingen Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery just outside of Soltau, Germany.

To e-mail Lawrence's nephew, Dave Olson